- Home

- Andrea Darby

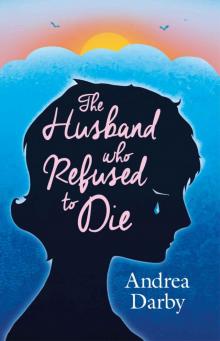

The Husband Who Refused to Die Page 2

The Husband Who Refused to Die Read online

Page 2

‘Yes, it was,’ I’d said. But was it? I wish I’d known what Dan wanted. The cryonics procedure had been planned, down to the last daunting detail – but what next? What about the farewell and finality for those left behind? Not even a few scribbles on one of his Post-its to guide me.

We should have discussed the funeral. It was my fault. I didn’t ask; maybe didn’t listen. But then, who knew it would all happen so soon? We were both supposed to die in old age, worn out and weary, but much wiser.

I’m grateful to Mum, Imogen and Mark for taking over with arrangements. I was incapable. Without them, there wouldn’t have been a memorial. And the vicar was so understanding. It wasn’t a circumstance he’d ever encountered, he’d said, suggesting the low-key service in the church’s adjoining prayer room.

‘But was any of it really right?’ I wonder as I sit, at last, on the sofa bed, still in my dark clothes, Dan’s brightly-coloured fitness equipment filling the room, yet accentuating the emptiness.

No body, no coffin, no earth, no ashes, no stone carved with the permanence of an epitaph. No drawing of curtains. No laying to rest.

You’re not in heaven, and what the hell do I do without you now, Dan?

CHAPTER 2

6 months later

I dally outside the whitewashed building, waiting for a sign; a spur. Perhaps the sun will break through the morning haze and light the way, or a voice inside my head will order me in. An empty juice carton passes in the gutter, dragged by a swirly summer breeze, then stops in the recess of a drain.

A car horn sounds in the distance. Several urgent blasts. ‘Go on!’ it says. ‘Do it!’

I gather the courage to enter, legs impossibly heavy, carrying so much fear – and hope – as I climb the twisted stairs.

Opening the only door, I see a group of around ten people sat in a neat circle on assorted chairs. An awkward hush is broken by a woman with short, feathery hair and kind blue eyes that match her plain blouse.

‘Hi, I’m Ingrid – you must be …’ she glances at her clipboard, ‘ … Carrie?’

‘Yes.’ I head across the patterned carpet to the empty chair, needlessly smoothing down my jersey top and wishing I’d been brave enough to arrive earlier; or not at all.

‘You haven’t missed anything,’ Mrs Clipboard says. ‘We were waiting.’ She straightens in her chair. ‘Before we start, as I always say, coming here’s a sign of strength, not weakness. This is a non-judgmental environment, somewhere to explore your emotions ...’

My eyes wander to the pale green walls, the matching curtains and frameless pastel painting above the suited man sat opposite, his shoes gleaming beneath grey socks. To his right sits a woman wearing nautical stripes and loafers. Her hair’s like mine; a low maintenance bob, with blonde highlights. She looks over, giving a gentle ‘join the club’ smile. I hear sniffles next to me, catching a glimpse of a fleshy cheek and frizzy hair and inhaling a floral scent that momentarily masks the damp air in the room.

Mrs Clipboard catches my eye. ‘We’re all here to share our grief, thoughts and experiences in a supportive way,’ she says.

Yes, and I’m here because I don’t know what else to do. Mum suspects I’m not coping despite the smiles I coax on to my face. And she’s right. I’m here because the advice and support from friends has been great, but it’s not enough, the positive morning mantras my sister-in-law Sunny prescribed don’t work for me and the medication from the doctor is dulling my senses and I hate functioning in this fog.

‘As we have two new people today, I think it would help if everyone introduced themselves and told us who they’re grieving for. That’s if you’re happy to.’ Mrs Clipboard sweeps her eyes around the circle, her crow’s feet a testament to the persistence of her warm smile. ‘Anyone?’

I swallow hard. Mrs Stripes introduces herself. She’s lost a husband. Others oblige: a son killed in a car crash, a brother by a genetic heart problem, a mum lost to cancer, the suited man had also lost his wife to the disease. The lady next to me chokes on her words. Her husband went in for a routine operation, but never came round. Tears turn to sobs. ‘He should still be here.’ Her fractured voice grows angry. ‘They took him from me.’ Mrs Clipboard offers tissues. The woman apologises.

‘Please don’t apologise. Emotional outbursts are natural. They’re not censored.’ Mrs Clipboard utters more soothing words. She has a suitcase full of them, it seems. But her compassion feels genuine; comforting. The drama’s distracted my nerves, but it’s my turn. My pulse accelerates.

‘My husband died six months ago,’ I say, gaze darting uncomfortably. ‘It was his heart.’ Mrs Clipboard urges me to continue with a gentle nod. I hesitate. ‘His body’s been frozen.’ A few shuffles. Mr Suit coughs. I expect surprised looks, frowns, sneers perhaps, but I see mostly blank, distant expressions.

‘I see … so …’ Mrs Clipboard flashes a kind smile.

‘He believes he can be brought back to life.’

She nods supportively. ‘And do you share that belief, Carrie?’

‘No … I mean, I’m not sure.’ My words seem to have pushed the others further away. I’m straining to see them, and not sure they can see me any more. Maybe they think I have some fine fragment of hope that they don’t. But things feel just as hopeless for me, I want to say.

I drift inwards, filling my lungs to calm the adrenalin. It feels as if we’ve been playing a game of bereavement snap and I’m the card without a match. I hear scraping chairs. People are moving and Mrs Clipboard’s asking us, in pairs, to consider what we miss most about our loved ones.

A shy young woman sits by me, chin down, twiddling with the tie cords of her hoodie. She misses her mum’s lasagne, her singing around the house, their chats. I miss Dan’s strong arms folding around me, his earthy, sweet smell that conjures up burnt toffee popcorn, the rasping, comedy kisses he landed on my neck in daft – and difficult – moments. I can’t stop. I miss his advice, his knowledge, sharing things with him; thoughts, problems – a slice of carrot and walnut cake with coconut milk icing (Dan had gone off the sugary stuff). At times, I even miss his tidiness and ‘to do’ lists. Finally, Mrs Clipboard hands out leaflets.

‘I hope you’ve found today helpful. It can be daunting, but I assure you it gets better. Remember, we’re all in the same boat.’ Her eyes seem to avoid mine.

Relieved it’s over, I shove the leaflet in my bag on my way to the door. In the street below, I collide with a man staggering from the betting shop, his beer breath hurling obscenities at me. Rushing past a few more people, I stop to sit on a low stone wall.

Somehow, I feel even more lonely in my sorrow than before I’d entered that room. I’m not in the same boat. They’ve all lost a travel companion, searching for strength as they make their way back to shore to begin a new life. I’m still floating.

***

It’s several hours before I can face my sister-in-law. I don’t feel like company, particularly hers, but I accepted her invitation to tea several days ago and feel it’s too late to cancel.

Sunny greets me at the door in a heavily patterned blouse with fussy purple embroidery around its loose neckline. With my mood so dark, I want to turn down the brightness – not just of Sunny, but all the possessions in her tiny lounge; burners and candles in sparkly containers, odd-shaped crystals and surfaces covered with garish drapes and throws. I often joked that I was scared to stand still for long when I visited, in case she wrapped me in something more colourful and outrageous.

‘So, how was the group counselling?’ Sunny drifts over to clear clutter from the sofa.

‘I’m not sure it’s for me.’

‘You’ve got to give it a chance, sweetness.’ Sunny gestures for me to take a seat.

‘Perhaps.’

Later, we’re sat with bowls of lentil casserole perched on two patchwork pouffes by our knees, surrounded by throws and tassels, and I’m relaying how Eleanor’s beginning to feel more settled at secondary school when Sunny rea

ches over, rubbing my leg with her bony fingers. Two earnest eyes stare out from a mass of crazy caramel curls and she does one of her slow-motion blinks.

‘Dan told me he was convinced cryonics would give him a chance to live again, but it wouldn’t be the same if you didn’t … you know, join him, Carrie.’

‘I’m grieving. Just let me grieve,’ I say firmly, taken aback, but trying not to get angry, to spoil her gesture of goodwill. She pats my leg, as if to say sorry, and we continue eating in silence.

My wounds are gaping and raw, and it feels like Sunny’s rubbing one of her citrusy oils into them. Not for the first time. Three weeks ago, while looking after Eleanor, she had the audacity to wear the ‘cryonics emergency procedure’ bracelet Dan kept in his bedside drawer. She’d asked for it as a keepsake, along with a pair of engraved cufflinks. I didn’t imagine she’d wear it, but I returned home late after an editorial meeting to find it hanging from her wrist. Eleanor was deeply upset, and, of course, I got it in the neck.

‘Why didn’t you keep it?’ she’d yelled, screwing up her lips and glaring through tearful eyes. ‘I hate you.’ It’s the first time she’s said that. Not one I’ll ever forget.

I leave Sunny’s soon after the meal, taking a detour so I can be alone at the wheel for longer. Swinging the car on to the drive, I miss the thrill I used to get pulling up outside our home. Replaced by a sinking feeling, and an echoing emptiness as I open the front door.

Yet it’s gorgeous; one of two double-fronted houses in the ash-tree-lined street, designed by a local builder. It was love at first sight for me – modern, yet elegant, with Georgian-style windows (perfect for my pencil pleat curtains), an arched porch, lawns front and back, a huge garage for Dan’s cars and all the mod cons inside to keep a lazy wife happy. Mum was smitten when she first saw it too. ‘Haven’t you done well for yourself?’ As if I’d finally achieved something. But I couldn’t take the credit. Dan’s business success had paid for it. He had enough drive for both of us. He was shrewd too. I guess I was his slightly ditsy blonde – not dumb, just not as smart as Dan.

Soon after she arrives home, Eleanor asks if Bethany can come round, despite my ‘no friends on a school night’ rule.

‘Please, just for a short while.’ She sweeps her fringe melodramatically, pleading with doe-brown eyes that are so much like her dad’s. ‘She’s really upset about something. She needs me.’ She looks so earnest, I have to titter.

‘And the “teen who can turn it on” Oscar goes to Eleanor Colwell,’ I tease. Eleanor curls her lip.

‘Has anyone ever told you you’re not funny?’

‘Yes, many times, but it doesn’t stop me.’ I know her surly “I’ve lost my dad so cut me some slack” face is a flick away, to be followed, no doubt, by a strop. I give in; hop on my Conflict Dodgem. Again. ‘OK. Only until eight.’ Always was one to fall for an actor.

The two girls spend most of their time applying make-up – still a novelty for Bethany who’s forbidden to wear it – and Eleanor then spends almost as long taking it off, her face puffy and red as she heads for bed.

After consoling myself with wine, I call Imogen, telling her how difficult I’d found the counselling, and what Sunny had said.

‘What a thing to say. What an insensitive …’ Imogen stops and I picture her steaming as she stands by the oven in full multi-task mode, a raised shoulder pinning the phone next to the short flicks of her choppy chestnut hair, one sturdy hand stirring something delicious in a pan, the other brushing a perfect glaze on to freshly-made pastries lined up on a baking tray for tomorrow’s breakfast.

‘Yes, it seems Sunny’s on some sort of “Convert Carrie to Cryonics” crusade. She clearly thinks it’s her duty to ensure I honour Dan’s wish.’

‘How dare she! Dan accepted you weren’t keen to sign up. She should too.’

‘But Dan assumed he had time to persuade me – several decades at least. We both did. And I thought he’d go off the idea, ask for a refund and buy a Maserati instead.’ I grimace at my flippancy.

‘I bet Sunny’s not signing herself up any day soon,’ Imogen says. ‘She’d surely prefer some higher, spiritual sequel to this life, a space filled with fairy dust and candlelight where she can float around freely and look down on us lesser mortals.’

‘Cruel.’

‘Seriously, you need to put her right, let her know how much she’s hurting you.’

‘You know I’m rubbish at confronting people,’ I say. ‘I hate the drama. Besides, she’s family, she was special to Dan – his baby sister – and I think she means well.’

‘Really?’ Imogen humphs.

After our goodbyes, I find myself looking through all the condolence cards, still in a pile under the coffee table. Some I can’t recall. It’s reassuring to re-read the sincere sympathies and heartfelt thoughts and prayers, to take in the comforting images of candles and crosses. Everyone seems so sure Dan’s gone forever. I guess there aren’t special cards for someone who believes they’ll come back.

I reach for the card at the bottom of the pile. Belated. A single, fuschia-pink flower curled across the front. I shoo away the inappropriate flutter as I hold it. Inside, his brief message; the familiar thin sloping letters – no curls on the descenders: ‘So sorry for your loss. Ashley.’ He had so much more to be sorry for.

At first, I’d been baffled by how he’d got my address, but then I realised it was because Dan’s story – our story – had been splashed across so many newspapers. And that same caption: Businessman Dan: ‘I’ll be back’. The one that was full of hope. I take the card upstairs, shutting it away in my bedside drawer.

Pulling on my dotty PJs, the familiar feeling of dread descends. I miss Dan so much more in the dark. I miss the sex too. I used to initiate it more than he did, often with a gentle nibble of his left lobe, though he rarely complained.

I lift Mr Fluff off the pillow, relishing the comfort of his beady eyes on me. He was an engagement gift, a cuddly toy dog with copper-coloured fur. Sadly, he’d become matted and seriously deformed, with limp legs and a fat tum where the stuffing had migrated. Eleanor had insisted on taking him to bed until she was about ten, declaring herself too old for teddy toys one night and flinging him back at me in horror.

Mr Fluff beckons my mind back to the hotel in Suffolk, the one Dan had spent about a fortnight’s wages for us to stay in for two nights …

He’d suggested an evening stroll around the grounds and I was following him, carrying my heels up the steps that led to a weather-worn statue of a nymph, coloured gravel replacing water in the pond she emerged from. We’d both dressed up, Dan dapper in suit trousers and a favourite white button-down shirt, me in a floral tea dress bought for the occasion.

I recall looking back at the hotel, topped by a white summer sky, the burnt reds of the original bricks blending with the new additions in near perfect harmony. The grounds had a delightful formality – several lush, lawned areas and rectangular rockeries bordered by box hedges and neatly trimmed topiary. I felt giddy, unused to wine then.

I turned to see Dan retrieving a small green box camouflaged in the crook of the nymph’s mossy arm. He dropped to the ground, one knee bent beneath him.

‘Will you make me the happiest man alive and be Mrs Carrie Colwell?’

‘Ye … yes, I will … do.’ The shock almost winded me. I hadn’t seen it coming, the set and staging so perfect; a water nymph bearing gifts. In the box was a large, luminous diamond, an oval set high on a gold band with tiny stones sparkling at the sides, as if lighting the way to the main attraction.

Dan smiled, sliding the ring along my shaky finger. ‘I hope you like it. Imogen helped me choose it.’

‘Sneaky lady – I had no idea.’ I stared down, hand trembling. ‘It’s so beautiful. I love it. And I love you.’ I giggled childishly.

‘Me too.’ Dan kissed me, then held me tight. The excitement of the event was twisting and turning inside me.

‘Can I keep my surnam

e?’

‘Really?’ Dan looked crestfallen.

‘No – just joking, you daft devil. I like a bit of alliteration.’

‘You like a bit of the other too,’ he said, dimples stretched with a zipped-up grin. ‘Come on.’ He took my hand, his curved to negotiate the diamond for the first time.

In our hotel room, I was greeted by Mr Fluff, brown coat vibrant against the ivory satin pillowcase.

‘You said you’ve always wanted a dog.’ Dan grinned.

I picked up the toy, breathing in the word ‘Fiancée’ on a tag hanging from a blue collar.

‘That was a bit presumptuous,’ I said. ‘What if I’d said ‘no’?’

‘I’d have asked someone else – that ring cost a fortune.’

I thumped Dan playfully, pushing him back on to the quilt. We made love for hours, at one point becoming a threesome, Mr Fluff appearing between us as we rolled over on the bed.

Later, after drinking fizzy wine that Dan had smuggled into his holdall wrapped in his university towel, he asked what I fancied doing the next day.

‘How about the theatre?’ I suggested.

‘I wondered about that walking history tour. It’s such an interesting town.’

The tour it was. Interesting it wasn’t – not that I remember much about it.

In fact, did it happen like that at all? Had I suggested the theatre, or just thought it? Was it a warm evening and did Dan wear the white shirt? Things were starting to blur, facts and feelings that once stood out with clarity, like red jewels on a silver plate, now fading too fast, lost in a mosaic of clashing colours.

I reluctantly return from the journey in my head, laying Mr Fluff on the empty side of the bed. I can see his collar again, and the word fiancée – though it’s not there; first frayed, then torn off in a vigorous washing cycle after Eleanor had spewed on him during a bout of tonsilitis.

The Husband Who Refused to Die

The Husband Who Refused to Die